Collecting Korean Wallpapers

GOSATE: Kang Dong-soo

We met Mr. Kang Dong-soo, a collector of Korean wallpapers. We stepped into a two-story warehouse in the old downtown of Gwangju and inhaled the scent of aged paper, steeped in history, as we explored his archive

frice is on a quest to find those who collect Korea. We discovered various collectors who capture Korea’s essence from their unique perspectives. Among them, we found a collector who writes a diary about hanok remodeling. What caught our attention was the story of archiving wallpapers from the hanok renovation process. frice immediately set off for Gwangju Metropolitan City to meet this collector. There, we met Mr. Kang Dong-soo, a devoted collector of Korean wallpapers. In a two-story warehouse in Gwangju’s old downtown, the air was filled with the scent of aged paper as we explored his archive. Each drawer held wallpapers collected under individual names and stories, and as we listened to their narratives, culture revealed itself.

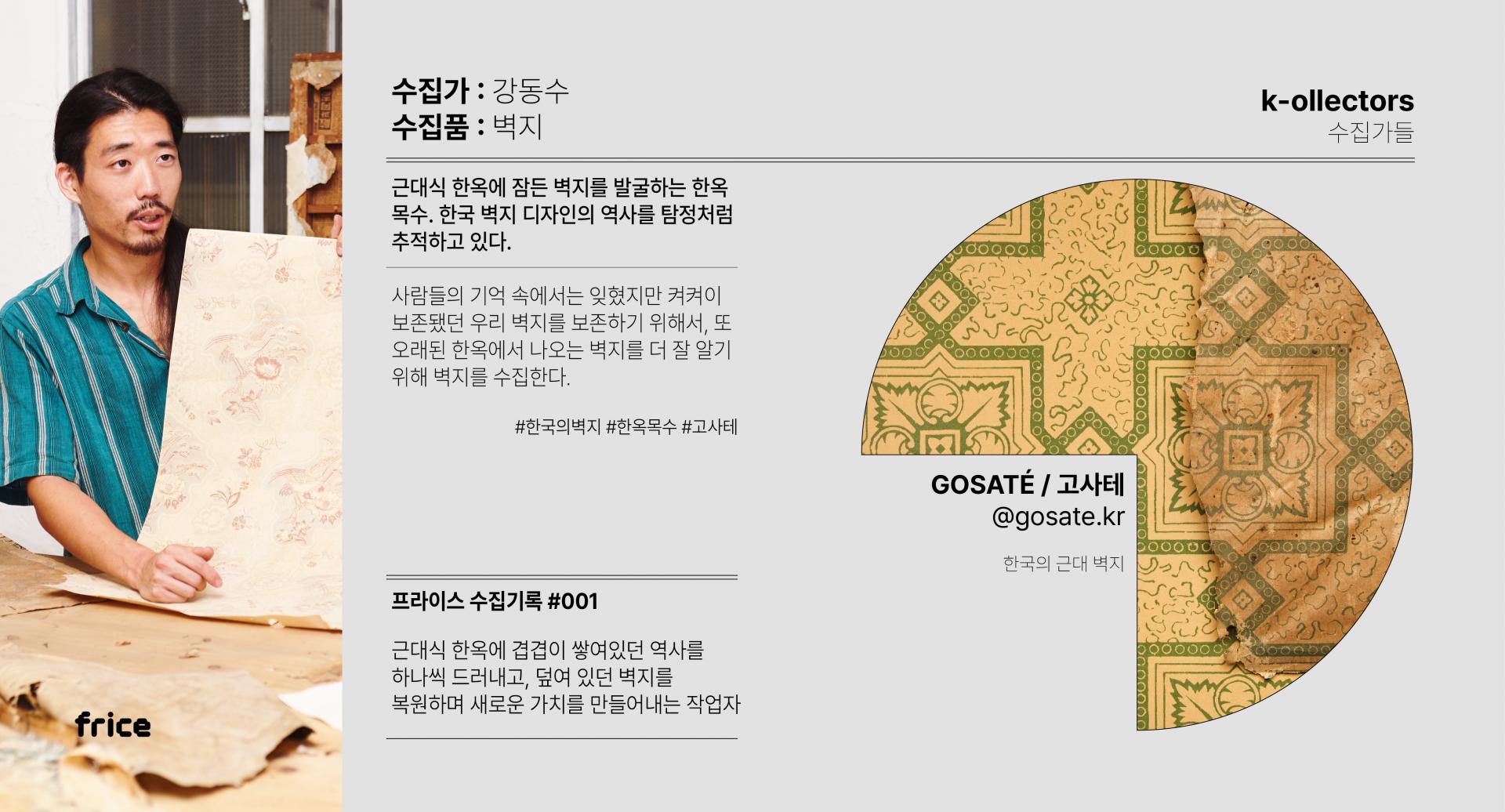

Could you share a bit about yourself?

I am Kang Dong-soo, a hanok carpenter. I collect wallpapers discovered in hanoks. From my collection, I created a wallpaper brand called GOSATE. GOSATE means “in the alley” and is derived from the native Korean word “고샅,” which means “alley.”

Interior of a Gangjin Hanok’s Sarangbang from 1946. Various patterned wallpapers remained completely intact. ⓒgosate

Collecting Korean wallpapers is fascinating. I’m curious about what sparked your interest in collecting them.

In 2022, I remodeled an old hanok in Boseong, Jeollanam-do. During the demolition of the living room, I discovered some French-style wallpaper, which I casually kept without much thought at the time. Later, while using scrap wood from the hanok repair as kindling for a campfire, unusual pieces of wallpaper began falling out of a pile of paper. My wife, who is French, looked at the paper carefully and said, “It seems that the wallpaper from the living room is not just ordinary kindling.” So we put out the fire and took another look. After collecting the burnt remnants and examining them, I realized that each piece carried its own story and value. Since then, I have started to collect wallpapers from hanok remodeling projects.

Original and restored wallpapers discovered on Gyodongdo in Ganghwa County, Incheon. The Russian Orthodox cross pattern and the peony pattern—shaped by Manchu–Chinese influences—are classic examples of wallpaper designs born from the Russian–Manchu sphere of influence.

TALK1. Why Do I Collect Wallpapers?

What do you pay the most attention to when collecting?

I pay the most attention to the historical context. Unlike in the West, in Korea, wallpapers are layered on top of each other, preserving their historical significance within each layer.

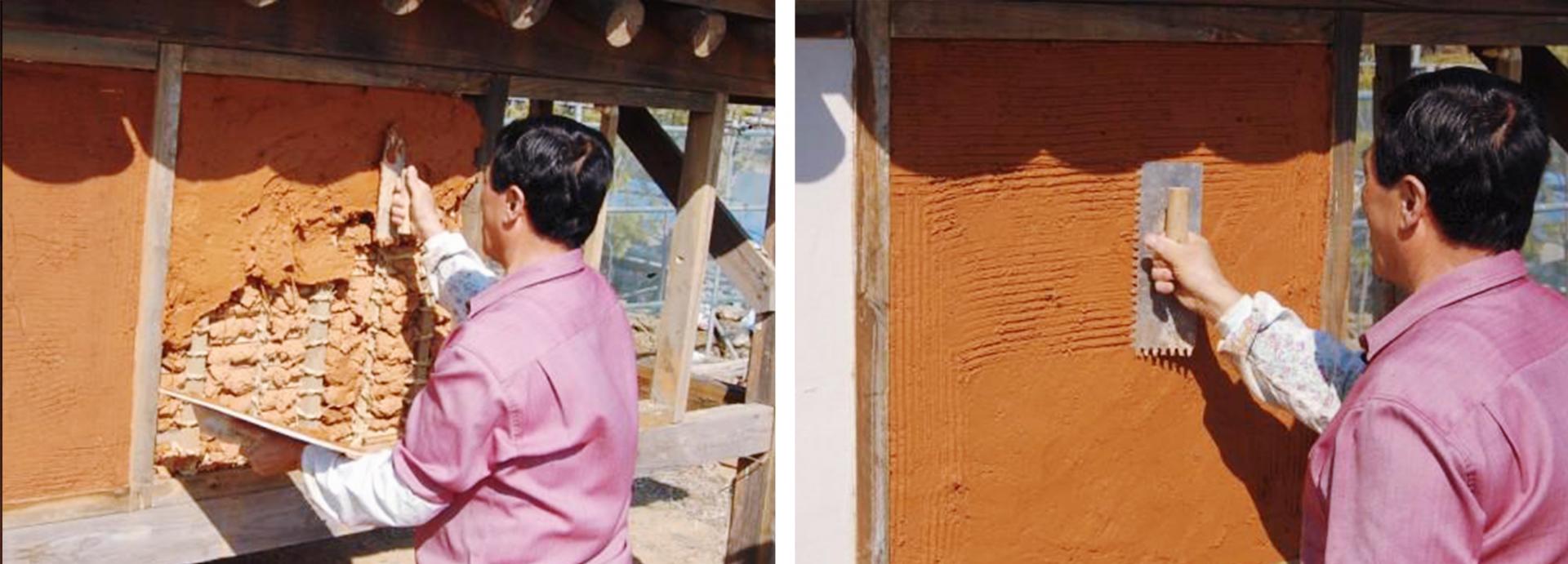

The reason for applying wallpaper in layers lies in the architectural structure. In Western architecture, wallpapers are affixed directly to solid walls, making them relatively easy to remove without extra layers. In hanoks, however, there is a framework called “인방 (inbang)” between the pillars. The space between this frame and the pillars forms the wall, which is then fitted with a bamboo lattice and finished with mud and other finishing materials. Because removing the wallpaper would also strip away the underlying earthen layer, it was instead applied on top. Additionally, layering the wallpaper provided insulation, serving a practical purpose.

“인방 (inbang)” refers to the horizontal beam that spans between pillars. In other words, it supports the pillars from the top, middle, and bottom, uniting several pillars to help resist lateral forces. (Reference: Traditional Culture Portal)

Earthen walls are the most widely used wall system in traditional Korean houses. A horizontal beam, known as “inbang (引枋),” is inserted between the columns of the earthen wall. ⓒHanok School

Urban-style hanok in Gwangju after remodeling. The pristine white walls are supported by inbang (horizontal beams) and pillars. ⓒfrice

Thus, the wallpapers found in traditional Korean houses bear witness to the history of the home and the passage of time. When you peel off the wallpaper, you reveal underlying layers—old newspapers, paper once used for drawing, or paper that served for calligraphy practice. In a literal sense, it’s a blend of histories, which is exactly why wallpaper archiving is so fascinating. Collecting wallpapers from hanoks often uncovers archival materials with significant documentary value.

Patterned wallpaper and backing paper remain on the hanok pillars in Wonseo-dong, Seoul. A newspaper printed with a TV program schedule offers a glimpse into the house’s history. ⓒfrice

We didn’t limit the application of paper solely to walls. Paper was also applied to furniture and even chests. Items intended to be elegantly wrapped often featured decorative patterns. In the Joseon Dynasty, chests were commonly adorned by cutting and pasting colored paper to create designs. With the advent of modern printing technology, patterned paper—printed with ink much like wallpaper—began to be applied as well. Without disturbing this historical context and preserving the original state as much as possible, I collect wallpapers from traditional Korean houses.

A 1950s-style paper container (紙函) unearthed by Mr. Kang Dong-soo at a hanok demolition site. This manufactured item follows the Joseon tradition of the Osaek paper container. It offers insights into the printing technology, ink quality, and design style of the period. ⓒfrice

Could you introduce one of the design-significant items from what you’ve collected and documented?

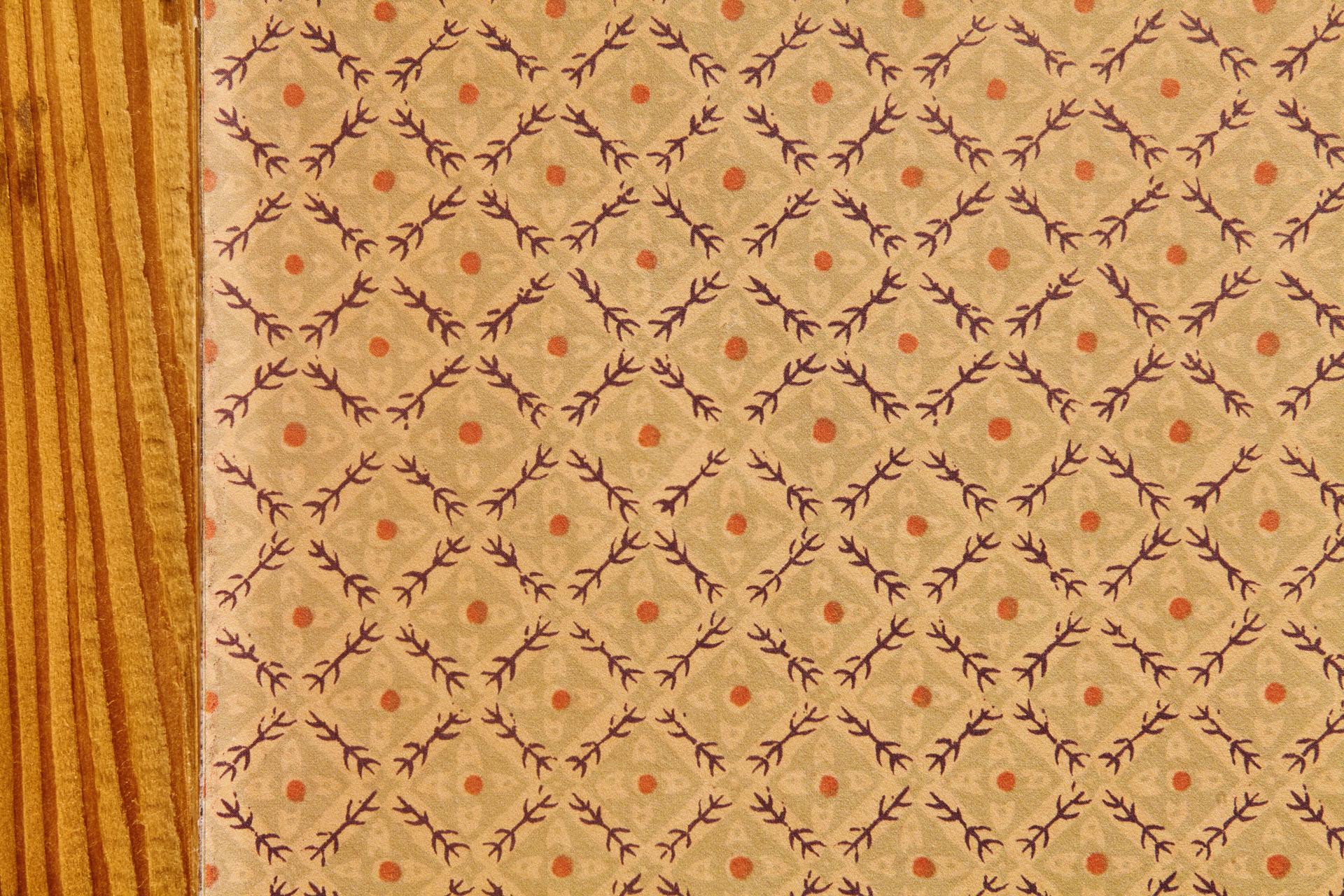

This is a 1950s design wallpaper that we named “점순(Jeom-sun)” at GOSATE. It was discovered in a modern hanok in Heungwang-ri, Ganghwa Island, built in 1945.

‘Jeom-sun’ patterned wallpaper, personally applied by Mr. Kang Dong-soo. It can be experienced at Manisambang, a multi-cultural space in Heungwang-ri, Ganghwa-do. ⓒfrice

The patterned wallpaper features hints of purple—reminiscent of the fountain pen ink we used to use. It’s essentially a black with a subtle purple tint, and the original wallpaper is noticeably more vibrant than the reproduction version. This wallpaper was designed in line with the aesthetics of that era.

The 1950s were marked by liberation and war, a time when resources were scarce and international exchange had been largely cut off. This meant that materials previously imported had to be produced domestically. With an established model patterned wallpaper already in place, replication was the way to go, but there was a significant shortage of consumables like the ink used in wallpaper production.

Korean-made wallpapers from the 1950s are generally characterized by pale hues and a minimal use of color. Their pattern designs tend to be simpler and more concise compared to those from other periods.

A fragment of the <농민주보> newspaper, unearthed alongside the patterned wallpaper. The article titled “Let’s Learn Our Language” and its content offer insights into the post-liberation era. ⓒfrice

The newspaper used as the backing paper behind the patterned wallpaper holds historical significance. <농민주보> was a publication issued during the first winter after liberation by the U.S. military government. In fact, <농민주보> was the inaugural issue—and it’s the first such document ever discovered in the country. Additionally, <황민일보>, which was unearthed alongside it, was a propaganda newspaper published by the Japanese colonial authorities to mobilize the colonized people for war.

Both of these documents serve as historical records that testify to the chaotic state of the times, and I can’t help but wonder what stories led these papers to become part of this house’s wallpaper. The fact that different periods are preserved together in one home after liberation is incredibly powerful, and it’s this very reason that I feel a deep connection to the wallpaper excavated from the hanok in Heungwang-ri, Ganghwa Island.

The backing paper that had lain undisturbed on the hanok building’s wall. It appears that the paper holds many stories. On the very front sheet, the traces of a painted Taeguk pattern are clearly visible. ⓒfrice

There are many items in our collection that capture the spirit of their era. Could you introduce some of the others as well?

Take a look at this one where the flag has been changed from the Iljanggi to the Taegukgi. This textbook, published by the Governor-General of Korea during the Japanese colonial period, was repurposed as backing paper—an educational resource from the colonial era. I’d love to explore further how Japan influenced Korean wallpaper culture.

Interestingly, Mitsubishi—a major conglomerate during the occupation—had its own wallpaper division. This is just my conjecture, but I suspect that wallpapering wasn’t a mainstream interior practice in Japan at the time. In Japan, wallpaper was typically reserved for the so-called “washiki” style or for Western-style buildings for the elite, and it was rare to see traditional wooden houses adorned with wallpaper like in Korea. In that sense, applying Western-patterned wallpaper in hanok rooms shows a certain openness in our culture.

Wallpaper was distributed separately to Korea by large companies like Mitsubishi, and there were even direct imports from Japan. My hypothesis, drawn from my work with these wallpapers, is that these imports weren’t intended for Japanese consumers at all—they were specifically designed with Korean buyers in mind. After all, when people are willing to invest in design, the trends tend to follow that market.

TALK2. The Method of Documenting Wallpapers

A space for collecting patterned wallpapers unearthed from hanoks. ⓒfrice

I wonder how you store such precious collectibles.

I have set up an archive space in my residence in Gwangju, where I keep the collected wallpapers on dedicated shelves. I label each shelf with the excavation site’s regional name and store the original wallpapers—once the peeling process is completed—sorted by layers.

The collected wallpapers are organized in cabinets with labels by region. ⓒfrice

Initially, I stored the layered, peeled wallpapers by simply stacking another wallpaper on top. However, as this method became increasingly inconvenient for retrieval, I built a custom storage platform using wooden plywood measuring 2,440mm in width and 1,220mm in height. Since nothing suitable was available on the market, I made it myself. The system consists of 15 levels of sliding shelves with two trays on either side that open outwards.

Unearthed wallpapers arranged in sequence and spread out widely. ⓒfrice

The key point is that I regard the backing paper (초배지) and the wallpaper as one entity. At the excavation site, I bundle the papers that were attached to the walls in chronological order and store them as a set. I do not separate the backing paper from the patterned wallpaper because the historical context and the era embedded in both are significant—they are preserved together as a whole.

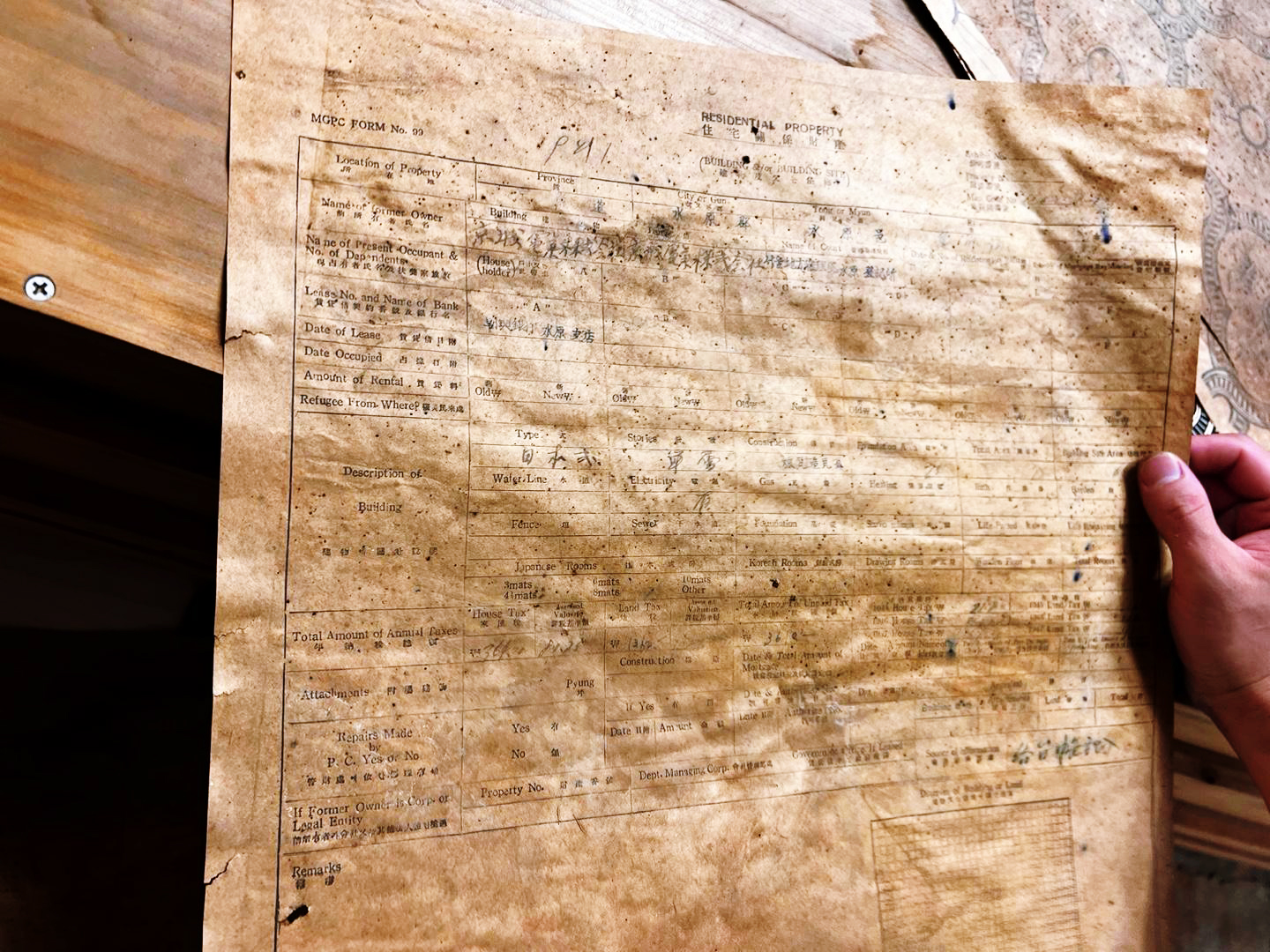

US Forces Korea’s Korean Architectural Building Registry used as backing paper. It was an important document immediately after liberation, but after the establishment of the Republic of Korea, it lost its official function. It is presumed that it was subsequently repurposed as wallpaper paper. ⓒfrice

For example, this particular backing paper is from a building registry published by the U.S. military government in the 1950s. It contains details used to distinguish whether a building is Korean-style or Western-style—whether it is a Japanese-style or a Korean-style house, the number of rooms, the naming conventions for different spaces, and even the underlying concepts and classification criteria of the house. It holds substantial historical value.

I store these items alongside the corresponding patterned wallpapers that were discovered with them. Occasionally, the manufacturer of the patterned wallpaper is identifiable—serving as a clue to determine if it is domestically produced or imported, and if domestic, whether it is from the Mugunghwa brand or the Baekjot brand. By following these clues, I can pinpoint the production period of the wallpaper.

The clumps of excavated wallpaper are kept in a corner of the storage room. Whenever I have time, I carry out the peeling process; once completed, I proceed with digital scanning and video recording. The original wallpapers, once safely archived, are then placed back into the wooden storage racks.

TALK3. What I Learned by Collecting Wallpapers

What value do you think the Korean wallpapers you’ve collected hold today?

They reveal so much about how we once lived. I believe that Korea’s wallpaper culture reflects a distinctly Korean way of life. While Koreans quickly absorb new designs from abroad, they tend to adhere to traditional standards and usages.

Patterned wallpaper featuring Songhakdo. On the left is a restored wallpaper sample by GOSATE, and on the right is an original wallpaper unearthed from a hanok demolition site. ⓒfrice

Take the “paper standard” as an example. The dimensions of the Western-patterned wallpaper excavated from hanoks follow the traditional measurements of hanji (Korean paper). If Western-patterned wallpaper were imported directly, it would likely have come as rolls spaced at 50cm intervals. However, the Western-style wallpaper affixed in old hanoks shows signs of being cut according to the conventional dimensions handed down since the Joseon Dynasty. It seems that architectural technicians of the time would cut each piece of wallpaper into rectangular shapes.

This fact is verifiable through archival footage. There is a recorded video from 1941—released by the Governor-General of Korea during the Japanese occupation—titled “Ondol.” It features scenes from hanoks, likely in Seoul’s Bukchon or Seochon neighborhoods, where rooms are being decorated. In those scenes, you can clearly see patterned wallpapers with designs and square-shaped wallpapers. From what I observed during hanok demolitions, it appears that square wallpapers were cut to standard sizes and arranged like a checkerboard to suit the room, with edges being joined gradually—pinched with wire or attached along thin slats—to form a grid across the wall.

Manisambang on Ganghwa Island featuring restored wallpaper installed by GOSATE CEO Kang Dong-soo. The wallpaper used in this room was excavated from this very house. ⓒfrice

The space where 20th-century wallpaper has been restored and installed, and its originals are carefully preserved, is truly impressive. ⓒfrice

Furthermore, the wallpaper culture is influenced by the ondol (underfloor heating) tradition. Wallpapers are closely tied to our way of heating individual rooms. Traditional Korean houses, compared to Western-style homes, generally have lower ceilings. In such settings, multiple layers of wallpaper were applied to maximize insulation—a practice almost unique to our country.

By tracing how paper was used in the spaces where Koreans once lived, one can observe the uniqueness of our residential environment. It is not just the design outcome of the wallpaper that is significant, but also the process by which it was affixed to the building’s walls and the background that made it possible. I find these elements profoundly Korean.

😈 Could it be that what once adorned our walls was nothing less than the “unconscious of Koreans”? I was really struck by how our age-old traditions can be discovered in the very paper originally meant for interior decoration, and by the collector’s dedication to tracing the backstory and original use of these pieces.

Kang Dong-soo’s collection of 20th-century patterned wallpapers isn’t just about gathering old items—it’s evolving into a fresh design project for interior wallpapers. I’m genuinely excited to see how far the designer’s passion for restoring the cultural context will go.

At GOSATE, we’ve put together a sample book featuring these restored wallpapers. If you’d like, you can even preserve the collector’s pieces as if they were part of an exhibition catalog. And the best part? The sample book is available for viewing! I recommend checking it out at CONCSEOUL in Hapjeong-dong, Seoul—visit the material library for designers there and experience the wallpaper catalog firsthand!

<👉 Check out the GOSATE Patterned Wallpaper Sample Book >

<👉 View CONC (CONC) GOSATE Restored Wallpaper Installation Case콩크(CONC) >

“Why do they collect Korea?” – Korean collectors discovered by frice. #K-ollectors #Collectors

Curated by frice

Photography: Han Chang-hwan

Location: Gwangju, GOSATE Archive